At just 16 years old, Charles Spurgeon was tricked into delivering his first very first sermon. Spurgeon recounted the tale in the March 1873 edition of The Sword and the Trowel. Read the story below.

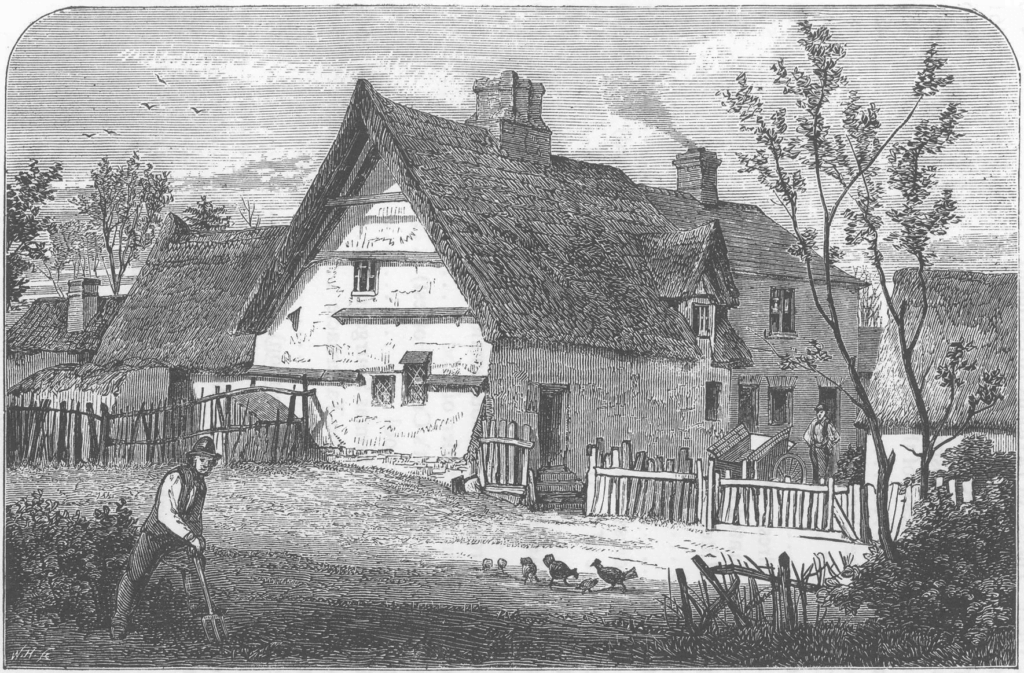

We remember well the first place in which we addressed a congregation of adults, and the wood-block which illustrates this number of the magazine sets it dearly before our mind’s eye. It was not our first public address by a great many, for both at Newmarket, and Cambridge, and elsewhere, the Sabbath-school had afforded us ample scope for speaking the gospel.

At Newmarket especially we had a considerable admixture of grown-up folks in the audience, for many came to hear “the boy” give addresses to the school. But no regular set discourse to a congregation met for regular worship had we delivered till one eventful Sabbath evening, which found us in a cottage at Teversham, holding forth before a little assembly of humble villagers.

The tale is not a new one, but as the engraving has not before been seen by the public eye we must shed a little light upon it. There is a Preachers’ Association in Cambridge connected with St. Andrew’s-street Chapel, once the scene of the ministry of Robert Robinson and Robert Hall, and now of our beloved friend Mr. Tarn.

A number of worthy brethren preach the gospel in the various villages surrounding Cambridge, taking each one his turn according to plan. In our day the presiding genius was the venerable Mr. James Vinter, whom we were wont to address as Bishop Vinter. His genial soul, warm heart, and kindly manner were enough to keep a whole fraternity stocked with love, and accordingly a goodly company of true workers belonged to the Association, and labored as true yoke-fellows.

Our suspicion is that he not only preached himself, and helped his brethren, but that he was a sort of recruiting sergeant, and drew in young men to keep up the number of the host; at least, we speak from personal experience as to one case.

We had one Saturday finished morning school, and the boys were all going home for the half. holiday, when in came the aforesaid “Bishop” to ask us to go over to Teversham next Sunday evening, for a young man was to preach there who was not much used to services, and very likely would be glad of company.

That was a cunningly devised sentence, if we remember it rightly, and we think we do; for at the time, in the light of that Sunday evening’s revelation, we turned it over, and vastly admired its ingenuity. A request to go and preach would have met with a decided negative, but merely to act as company to a good brother who did not like to be lonely, and perhaps might ask us to give out a hymn or to pray, was not at all a difficult matter, and the request, understood in that fashion, was cheerfully complied with. Little did the lad know what Jonathan and David were doing when he was made to run for the arrow, and as little knew we when we were cajoled into accompanying a young man to Teversham.

Our Sunday-school work was over, and tea had been taken, and we set off through Barnwell, and away along the Newmarket-road, with a gentleman some few years our senior. We talked of good things, and at last we expressed our hope that he would feel the presence of God while preaching. He seemed to start, and assured us that he had never preached in his life, and could not attempt such a thing: he was looking to his young friend, Mr. Spurgeon, for that. This was a new view of the situation, and I could only reply that I was no minister, and that even if I had been I was quite unprepared. My companion only repeated that he, even in a more emphatic sense, was not a preacher, that he would help me in any other part of the service, but that there would be no sermon unless I gave them one. He told me that if I repeated one of my Sunday-school addresses it would just suit the poor people, and would probably give them more satisfaction than the studied sermon of a learned divine.

I felt that I was fairly committed to do my best. I walked along quietly, lifting up my soul to God, and it seemed to me that I could surely tell a few poor cottagers of the sweetness and love of Jesus, for I felt them in my own soul. Praying for divine help, I resolved to make an attempt. My text should be, “Unto you therefore which believe he is precious,” and I would trust the Lord to open my mouth in honor of his dear Son.

I walked along quietly, lifting up my soul to God, and it seemed to me that I could surely tell a few poor cottagers of the sweetness and love of Jesus

CH Spurgeon

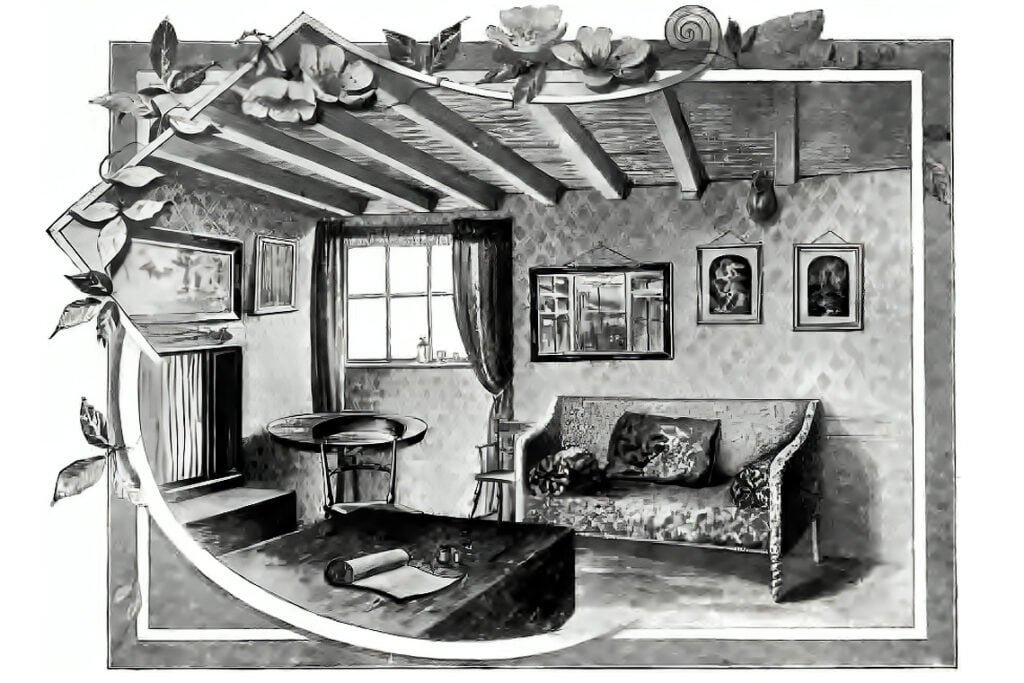

It seemed a great risk and a serious trial, but, depending upon the power of the Holy Ghost, I would at least tell out the story of the cross, and not allow the people to go home without a word. We entered the low-pitched room of the thatched cottage, where a few simple-minded farm-laborers and their wives were gathered together; we sang and prayed and read the Scriptures, and then came our first sermon.

How long or how short it was we cannot now remember. It was not half such a task as we had feared it would be, but we were glad to see our way to a fair conclusion, and to the giving out of the last hymn. To our own delight we had not broken down, nor stopped short in the middle, nor been destitute of ideas, and the desired haven was in view.

We made a finish, and took up the book, but to our astonishment an aged voice cried out, “Bless your dear heart, how old are you?” Our very solemn reply was,” You must wait till the service is over before making any such enquiries. Let us now sing.” We did sing, and the young preacher pronounced the benediction, and then began a dialogue which enlarged into a warm, friendly talk, in which everybody appeared to take part.

“How old are you?” was the leading question. “I am under sixty,” was the reply. “Yes, and under sixteen,” was the old lady’s rejoinder. “Never mind my age, think of the Lord Jesus and his preciousness,” was all that I could say, after promising to come again, if the gentlemen at Cambridge thought me fit to do so. Very great and profound was our awe of those “gentlemen at Cambridge” in those days.

Are there not other young men who might begin to speak for Jesus in some such lowly fashion—young men who hitherto have been mute as fishes? Our villages and hamlets offer fine opportunities for youthful speakers. Let them not wait till they are invited to a chapel, or have prepared a fine essay, or have secured an intelligent audience. If they will go and tell out from their hearts what the Lord Jesus has done for them, they will find ready listeners.

Many of our young folks want to do great things, and therefore do nothing at all; let none of our readers become the victims of such an unreasonable ambition.

He who is willing to teach infants, or to give away tracts, and so to begin at the beginning, is far more likely to be useful than the youth who is full of affectations and sleeps in a white necktie, who is studying for the ministry, and is touching up certain superior manuscripts which he hopes ere long to read from the pastor’s pulpit.

He who talks upon plain gospel themes in a farmer’s kitchen, and is able to interest the carter’s boy and the dairymaid, has more of the minister in him than the prim little man who talks for ever about being cultured, and means by that—being taught to use words which nobody can understand.

To make the very poorest listen with pleasure and profit is in itself an achievement, and beyond this it is the best possible promise and preparation for an influential ministry. Let our younger brethren go in for cottage preaching, and plenty of it. If there is no Lay Preachers’ Association, let them work by themselves. The expense is not very great for rent, candles, and a few forms: many a young man’s own pocket-money would cover it all.

No isolated group of houses should be left without its preaching-room, no hamlet without its evening service. This is the lesson of the thatched cottage at Teversham.